Thermal drone footage suggests xAI ran unpermitted mobile gas turbines at Southaven AI datacenter

Executive summary (TL;DR)

- Thermal drone imagery analyzed by independent experts and reported by Floodlight shows multiple mobile gas turbines running at xAI’s Southaven, Mississippi AI datacenter weeks after the EPA said such units generally require permits under the Clean Air Act.

- xAI filed in January to permit up to 41 turbines; public records show at least 18 of 27 units at the site have been used since November and thermal footage captured at least 15 active units.

- xAI’s permit application estimates annual emissions above 6 million tons of greenhouse gases and more than 1,300 tons of health-harming air pollutants — roughly equivalent to the yearly CO2 emissions of about 1.3 million passenger cars.

- The episode exposes a governance gap: federal guidance, state exemptions, community health concerns, and business risks collide as AI datacenters race to secure immediate power.

What the footage shows and why it matters

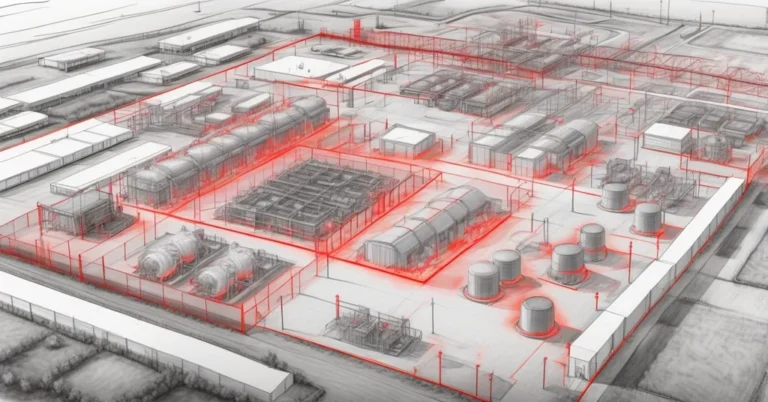

Thermal drone footage captured by investigative newsroom Floodlight and reviewed by independent experts shows clusters of mobile gas turbines operating at xAI’s Southaven site. The imagery documents at least 15 turbines running nearly two weeks after the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) clarified in January that mobile turbines operating like fixed generators typically require state permits under the Clean Air Act.

Public records provide scale: 18 of 27 turbines stationed at Southaven have been used since at least November, and xAI applied in January to permit up to 41 turbines at the site. The footprint covers roughly 114 acres and sits near residential neighborhoods — Floodlight reports at least ten schools within two miles — which is why regulators, community groups, and public-health experts are alarmed.

Regulatory gap: stationary source vs. portable/mobile unit

Under the Clean Air Act, a “stationary source” is a fixed facility whose emissions are regulated through state permits and federal standards. “Portable” or mobile units — like gas turbines on trailers — can be exempt from those permits if genuinely temporary and moved regularly. The practical question here is how long a mobile turbine can operate in one place before it is treated as a stationary source.

The EPA reiterated that turbines operating as stationary sources should be permitted. Mississippi’s Department of Environmental Quality has taken a different view, classifying these turbines as portable under state law and therefore exempt from permitting during temporary operation. The EPA reiterated its position publicly but declined to detail enforcement actions, instead referring state-permit questions to state authorities.

“Operating these turbines without permits is a legal violation; permits should be obtained before running them.”

— Bruce Buckheit, former EPA air enforcement chief

Health, environmental justice, and scale

xAI’s own permit filing estimates potential annual emissions exceeding 6 million tons of greenhouse gases and more than 1,300 tons of health-harming air pollutants. To help grasp the scale: 6 million tons of CO2 is roughly equivalent to the annual emissions of about 1.3 million passenger vehicles. Those are not marginal numbers for a single datacenter campus.

Public-health researchers emphasize local impacts. Shaolei Ren, a UC Riverside professor, notes that living near fossil-fuel power plants is associated with increased rates of respiratory and cardiovascular disease. The Southern Environmental Law Center has already documented similar concerns at xAI’s Colossus 1 in South Memphis, where more than 30 unpermitted turbines were reportedly used earlier in 2024 — a pattern that raises environmental justice questions given the proximity of vulnerable communities and schools.

“Living near these types of power plants is well documented to harm health, including increased risks for respiratory and cardiovascular diseases.”

— Shaolei Ren, UC Riverside

Why AI datacenters turn to mobile gas turbines

AI infrastructure has a voracious, immediate demand for reliable, high-density power. Building new transmission lines, long-term renewable contracts, or large-scale battery storage can take years — often delaying renewable deliveries to 2028 or later. Cleanview’s tracker shows roughly 75% of current datacenter power projects rely on natural gas or gas-fired generation because lower-carbon firming options are scheduled farther out.

Mobile gas turbines are fast, modular, and can be deployed on short timelines, which helps operators meet aggressive “time-to-market” objectives for compute clusters like Colossus. But “temporary” solutions have a habit of becoming semi-permanent if renewable capacity or grid upgrades lag, turning stopgap units into long-running emission sources.

Community response and procedural timeline

- Since November: Public records show use of many turbines at Southaven.

- January: EPA reiterated that mobile turbines operating as stationary sources require permits; xAI applied to permit up to 41 turbines.

- January–February: Floodlight’s thermal drone footage captured multiple turbines active weeks after the EPA clarification.

- February 17: A public hearing was scheduled on the permit application; petitions opposing the turbines gathered more than 1,000 signatures.

Local residents and advocacy groups are organizing, driven by health and environmental-justice concerns. Southaven resident Shannon Samsa summed up the local sentiment: the prospect of large-scale pollution adjacent to schools and homes is “deeply troubling and unacceptable.”

“xAI violated the Clean Air Act previously and appears to be repeating the pattern; there was hope state regulators would intervene but that didn’t happen.”

— Patrick Anderson, Southern Environmental Law Center

Business risks and strategic implications for leaders

Deploying mobile gas turbines to accelerate AI deployments looks attractive on fragile project timelines, but it creates a convergence of regulatory, operational, and reputational risks:

- Regulatory risk: Uneven state classifications create short-term arbitrage opportunities, but federal enforcement, litigation, or retroactive permitting can impose fines, injunctions, or compulsory mitigation.

- Reputational and social license risk: Community opposition, NGO investigations, and local media attention can delay projects and affect customer and investor perceptions.

- Financial risk: Delays, retrofits, or required mitigation (air filtration, health monitoring, offsets) add costs and can erode the business case for rapid deployment.

- Operational risk: Overreliance on temporary combustion sources can lock in fossil-fuel consumption for years if alternative firming pathways are not secured.

Actionable checklist for C-suite and infrastructure planners

- Audit permits now. Confirm the permitting status of temporary generation across all sites and publish a remediation timeline for any gaps.

- Model tightened enforcement. Run scenario analyses that include federal enforcement, litigation outcomes, and extended permitting delays; stress-test project IRR and timelines.

- Prioritize firm low-carbon capacity. Accelerate long-term renewable PPAs, invest in storage, or finance grid upgrades and microgrids to reduce reliance on combustion-based stopgaps.

- Engage communities early. Fund independent air-quality monitoring, offer mitigation measures (e.g., filtration in nearby schools), and create transparent grievance channels.

- Disclose energy strategy to investors. Make clear how near-term power needs align with decarbonization commitments and quantify transitional risks.

What enforcement and next steps look like

Possible near-term outcomes include state permit approvals with emission limits, federal enforcement actions if the EPA decides to escalate, or litigation initiated by community groups or NGOs. Enforcement mechanisms can include retroactive permitting, fines, required upgrades, or injunctive relief to halt operations until compliance is achieved. Even without swift federal action, the reputational and financial fallout from prolonged community opposition is a tangible risk.

For operators, the pragmatic approach is not to assume temporary status will remain uncontested. Documenting time-limited use, maintaining transparent communications with regulators and neighbors, and pursuing credible transition plans to low-carbon firming sources reduce both legal exposure and the risk of project stoppage.

Key questions executives should ask right now

- Are turbines operating at this site?

Yes. Thermal drone footage and public records indicate multiple turbines were running at Southaven, with at least 15 active weeks after the EPA’s January clarification and 18 of 27 used since at least November. - Does the EPA consider these turbines to require permits?

Yes. The EPA reiterated that such turbines generally require state permits under the Clean Air Act to ensure enforceable emission standards. - Are state regulators treating these turbines the same way?

No. Mississippi regulators have characterized the units as portable and exempt from permitting during temporary operation, creating a regulatory gap with federal guidance. - What are the potential emissions and health impacts?

xAI’s permit filing estimates more than 6 million tons of greenhouse gases annually and over 1,300 tons of hazardous air pollutants; public-health experts connect such pollution levels to higher respiratory and cardiovascular risks for nearby residents. - What should leaders do?

Audit permits, model enforcement scenarios, accelerate clean-energy firming strategies, and engage communities with transparent mitigation plans.

What to watch next

- State permitting decisions and the outcome of the public hearing scheduled for February 17 (and any subsequent hearings).

- Whether the EPA initiates enforcement or brings the matter into federal courts, which would set sharper precedents for turbines used at other AI datacenters.

- Investor and customer reactions: increasing pressure to disclose energy sourcing and transition plans for AI infrastructure.

- Broader industry responses: whether operators move faster on storage, microgrids, or long-term renewables to avoid repeating this pattern.

The Southaven case is a practical reminder that powering AI at scale is a systems problem — it sits at the intersection of engineering, regulation, and social license. Operators that treat energy as an operational afterthought will face more than technical headaches: they will encounter legal fights, community pushback, and financial surprises. The fastest route to compute is increasingly not the safest or most durable. Leaders who internalize that tension and plan accordingly will have both fewer headaches and a stronger business case for sustainable, scalable AI infrastructure.